Sunday, February 19, 2006

Waiting for Ghada

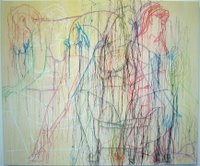

Ghada Amer depicts hot girl-on-girl action. Women pose spread-eagle, masturbate, suck each other's nipples, and sixty-nine each other. They make "O" faces and stick out their tongues, and indulge your fetishes by brandishing high heels, garter belts, jewelry, and dildos.

But the erotic mise en scene seem secondary to the technique of stitching into the linen. With multi-colored string, sometimes on a painted ground, Amer draws by sewing. The string delineates each figure, weaving around the forms and then joining hanging masses of tangled string. Occasionally, she paints over or under the stitched lines in chromatically intense washes. The figures often repeat across the surface, sometimes arranged on a grid, albeit with slight differences each time - limbs disappear, or a stiletto.

This repetition brings to mind Warhol, who repeated portraits, car crashes, and soup cans. The materials involved connect Amer to other stitchers, such as Orly Cogan, Kent Henricksen, and even Mike Kelley. And the circumstantial gender-specificity of sewing adds another dimension to the work. What is more "girly" than sewing? This cultural convention - that only females sew - because men are busy hammering and sawing - opens up a visual language with femininity at its source. (We're on thin ice here, wary of sexism.) Who was the last notable image-stitcher? Betsy Ross?

Yet the drawings aren't sexy, even if they are sexual. The women posing are generic and prototypical, devoid of personality. And with the reductive style of drawing, they seem more like advertising icons ready for a branding label. They aren't inviting. Moreover, male viewers are shunned when they realize that Ghada's sex kittens need no men. The women seem content with each other, or even alone. Finally, the serial repetition they suffer/enjoy causes the eyes a sexual "diminishing return." With each successive generation of the figure, we are less impressed, and detect the typical tedium of these moaning mavens.

But the erotic mise en scene seem secondary to the technique of stitching into the linen. With multi-colored string, sometimes on a painted ground, Amer draws by sewing. The string delineates each figure, weaving around the forms and then joining hanging masses of tangled string. Occasionally, she paints over or under the stitched lines in chromatically intense washes. The figures often repeat across the surface, sometimes arranged on a grid, albeit with slight differences each time - limbs disappear, or a stiletto.

This repetition brings to mind Warhol, who repeated portraits, car crashes, and soup cans. The materials involved connect Amer to other stitchers, such as Orly Cogan, Kent Henricksen, and even Mike Kelley. And the circumstantial gender-specificity of sewing adds another dimension to the work. What is more "girly" than sewing? This cultural convention - that only females sew - because men are busy hammering and sawing - opens up a visual language with femininity at its source. (We're on thin ice here, wary of sexism.) Who was the last notable image-stitcher? Betsy Ross?

Yet the drawings aren't sexy, even if they are sexual. The women posing are generic and prototypical, devoid of personality. And with the reductive style of drawing, they seem more like advertising icons ready for a branding label. They aren't inviting. Moreover, male viewers are shunned when they realize that Ghada's sex kittens need no men. The women seem content with each other, or even alone. Finally, the serial repetition they suffer/enjoy causes the eyes a sexual "diminishing return." With each successive generation of the figure, we are less impressed, and detect the typical tedium of these moaning mavens.