Thursday, March 23, 2006

Rowing in Eden

Youngsters at Judith Linhares' new show shared the same conversation: "Wow, these look just like Dana You-know-who..."

Both painters share relentlessly intense palettes; bold brushstrokes, and spontaneous drawing. Their figures are blocky, grotesque, and freakish. Both embark on flights of pastoral fantasy too ambiguous to be utopic. Mother nature and human nature can be refreshing, but also menacing.

Judith Linhares, in her 60s, has a fruitful career behind her - including 26 years in New York. Her work is in several museum collections. It's unlikely that she would opportunistically join Dana Schutz. On the other hand, this show's figurative work marks a departure from her previous oeuvre of still life paintings. Dana Schutz uses the figure almost exclusively. And with Schutz' vast press attention, surely Linhares is familiar with her work.

To avoid digressive speculation, let's just assume that Linhares and Schutz share similar influences, so similarity between them is inevitable. It may be more interesting to distinguish the differences between them.

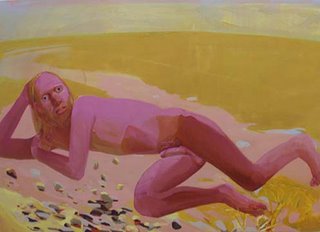

Compare Linhares' "Starlight" and Schutz' "Reclining Nude." Both paintings feature a nude reclining under a vast sky. "Starlight" stars a pink, nude female leaning back on a Mexican blanket, admiring the night sky. She is flanked by two squatting figures. In "Nude," Schutz' hero, Frank, also pink from sunburn, relaxes in the sand, before an ochre ocean. Schutz emphasizes the monumentality of Frank by stretching him beyond the borders of the canvas. Linhares' pink figure is more contained, which establishes the cast scale of the sky, and the massive moon hovering overhead. Linhares also considers light - her figure glows under the moonlight, while Frank seems to evade any light source. Both figures respond to gravity: the pink pixie's head dangles preternaturally; Frank's flaccid penis drapes over his extended thigh, as relaxed as Frank himself.

Their use of light distinguishes one painter from the other. Aside from dappled light filtering through trees to reach the figures, Schutz' figures generate their own light. They beam hot pinks and bright yellows, although some peer out from the darkness. Linhares' figures, on the other hand, bathe in powerful light sources, like the threatening bonfire in "Wild Nights." The inferno in the paintings seems to rage outside the boundaries of the logs meant to contain it. And the fire itself is a bold abstraction, with giant brushstrokes zipping across the surface, like a Karin Davie abstraction. The marshmallow-roasting campers join the viewer in pausing to admire this painterly bravura.

"Fools for Love" is the strongest painting in the show, with a mysterious narrative. Linhares fan Larry Lockridge described "Fools" as being "post-Edenic." Four females occupy a large tree. An innocent naif sits at the base of the tree, gazing dreamily towards the sky. Two brave women stand precariously at ends of the branches, climbing upwards, but risking a broken branch. And at the top of this hierarchy is a vixen glaring down at the viewer. Her menacing face lurks against the dark tree trunk, lit from below in a hot orange color. The tree is a metaphorical upward climb, and suggests that a climber's progress depends on aggression, shrewdness, and intimidation.

Both painters share relentlessly intense palettes; bold brushstrokes, and spontaneous drawing. Their figures are blocky, grotesque, and freakish. Both embark on flights of pastoral fantasy too ambiguous to be utopic. Mother nature and human nature can be refreshing, but also menacing.

Judith Linhares, in her 60s, has a fruitful career behind her - including 26 years in New York. Her work is in several museum collections. It's unlikely that she would opportunistically join Dana Schutz. On the other hand, this show's figurative work marks a departure from her previous oeuvre of still life paintings. Dana Schutz uses the figure almost exclusively. And with Schutz' vast press attention, surely Linhares is familiar with her work.

To avoid digressive speculation, let's just assume that Linhares and Schutz share similar influences, so similarity between them is inevitable. It may be more interesting to distinguish the differences between them.

Compare Linhares' "Starlight" and Schutz' "Reclining Nude." Both paintings feature a nude reclining under a vast sky. "Starlight" stars a pink, nude female leaning back on a Mexican blanket, admiring the night sky. She is flanked by two squatting figures. In "Nude," Schutz' hero, Frank, also pink from sunburn, relaxes in the sand, before an ochre ocean. Schutz emphasizes the monumentality of Frank by stretching him beyond the borders of the canvas. Linhares' pink figure is more contained, which establishes the cast scale of the sky, and the massive moon hovering overhead. Linhares also considers light - her figure glows under the moonlight, while Frank seems to evade any light source. Both figures respond to gravity: the pink pixie's head dangles preternaturally; Frank's flaccid penis drapes over his extended thigh, as relaxed as Frank himself.

Their use of light distinguishes one painter from the other. Aside from dappled light filtering through trees to reach the figures, Schutz' figures generate their own light. They beam hot pinks and bright yellows, although some peer out from the darkness. Linhares' figures, on the other hand, bathe in powerful light sources, like the threatening bonfire in "Wild Nights." The inferno in the paintings seems to rage outside the boundaries of the logs meant to contain it. And the fire itself is a bold abstraction, with giant brushstrokes zipping across the surface, like a Karin Davie abstraction. The marshmallow-roasting campers join the viewer in pausing to admire this painterly bravura.

"Fools for Love" is the strongest painting in the show, with a mysterious narrative. Linhares fan Larry Lockridge described "Fools" as being "post-Edenic." Four females occupy a large tree. An innocent naif sits at the base of the tree, gazing dreamily towards the sky. Two brave women stand precariously at ends of the branches, climbing upwards, but risking a broken branch. And at the top of this hierarchy is a vixen glaring down at the viewer. Her menacing face lurks against the dark tree trunk, lit from below in a hot orange color. The tree is a metaphorical upward climb, and suggests that a climber's progress depends on aggression, shrewdness, and intimidation.