Monday, November 27, 2006

Currin Rakes It In

The sexual imagination of the Heterosexual Male is John Currin's playground. All women submit to His gaze, as irresistible as X-ray as it undresses its subjects, elaborating on the lace lingerie. In these paintings, women are pleasant scenery or fine china, literally: sharing a table top with the settings of a Dutch still life, a gangly model escapes Egon Schiele's studio to pose for Currin. Still, she's just another object, albeit less shiny. Yet simultaneously, Currin's fleshy nymphs, ladies, and broads brim with vivacious personality.

Each woman is oblivious to her sitting-duck objectification, too busy aching for a substantial man to appear and pound away her aching desire. Or she dreams of a buxom blonde. Girl-on-girl is just fine (as long as we can watch and as long as they are not ugly lesbians). But don't look for Jack Twist and Ennis Del Mar. Same-sex pairings evade men in Currin's new paintings; a second man never appears to compromise our champion.

Either way, the man is on top and the women are on their backs. One exception is "Copenhagen," a menage a trois in which one woman straddles the man. On top, she seems dominant. Another woman steers her onto the man's erection, empowered in this directorial role. So the man appears to be doubly submissive. These women so dominate the pictorial space that they swallow his head (er, both heads). But his erection prevails, refusing to surrender. It's like the ubiquitious folk poster, "Never Give Up."

Male painters easily make misogynistic mistakes, real or imagined. Currin trudges through this minefield oafishly, yet manages it with panache. He exposes his sexism, loud and proud. Like a butcher sizing up stock, Currin counts only the choice parts: perky tits, doe eyes, plump lips. And like Picasso, Currin tries to cram all the good stuff into the picture. Currin's dolls share a gaze that looks spacey, vapid, and needy. You don't laugh with them, you laugh at them.

On the other hand, Currin lovingly relishes the curves and bulges of the female figure. He models and renders form, and the figures burst from Currin's silvery palette, reminiscent of the lush "Barry Lyndon." All this care suggests sincerity that neutralizes his ironic tendencies. Compare to David Salle's murky, bland photorealism or Cotton's superacademic, hyperkitsch models, available in chocolate or strawberry. Meanwhile, DeKooning battered women down to fluid scribbles and angular strokes.

Does Currin love women or hate them? Rather, what does he love/hate about women? He said in a Flash Art interview: I don't love women, I just think about them all of the time.

I love to look at women; they stimulate my imagination and not just in a sexual way.

I used to love watching women hobbling in their new shoes down fourteenth street.

I saw myself in them. I get a perspective on myself when looking at a woman, her beauty, her ugliness, her failures.

Six or seven paintings - less than half of the show - are sex pictures. The others are "chick paintings," including a portrait of his fully clad spouse, in "Federal Rachel." Another clothed woman is the fruit-bearing brunette in "The Christian," a hilarious prude suffering the fornicating heathens. More hilarious is "Anna" a Christopher Guest-cast nerd in her late 30s who smiles all too warmly from behind a candlestick and ripe banana.

The clues to a narrative arc are two portraits of Currin's son, Francis, and a future portrait, "2070," where Francis appears as a post-sex old man. This, and the neighboring baby portrait are bookends to the chapters of adult sexual adventure of Francis, something like Hockney's or Hogarth's "The Rake's Progress" - maybe that's what Francis 2070 is reading! Alas, like Father, like Son; Francis likes his whores, but loves his Madonna - again, "Federal Rachel." He may be a womanizer, but our polyester-suited, gallant gentleman still courts his women with white wine and a sunny day.

Each woman is oblivious to her sitting-duck objectification, too busy aching for a substantial man to appear and pound away her aching desire. Or she dreams of a buxom blonde. Girl-on-girl is just fine (as long as we can watch and as long as they are not ugly lesbians). But don't look for Jack Twist and Ennis Del Mar. Same-sex pairings evade men in Currin's new paintings; a second man never appears to compromise our champion.

Either way, the man is on top and the women are on their backs. One exception is "Copenhagen," a menage a trois in which one woman straddles the man. On top, she seems dominant. Another woman steers her onto the man's erection, empowered in this directorial role. So the man appears to be doubly submissive. These women so dominate the pictorial space that they swallow his head (er, both heads). But his erection prevails, refusing to surrender. It's like the ubiquitious folk poster, "Never Give Up."

Male painters easily make misogynistic mistakes, real or imagined. Currin trudges through this minefield oafishly, yet manages it with panache. He exposes his sexism, loud and proud. Like a butcher sizing up stock, Currin counts only the choice parts: perky tits, doe eyes, plump lips. And like Picasso, Currin tries to cram all the good stuff into the picture. Currin's dolls share a gaze that looks spacey, vapid, and needy. You don't laugh with them, you laugh at them.

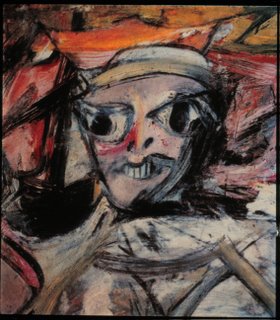

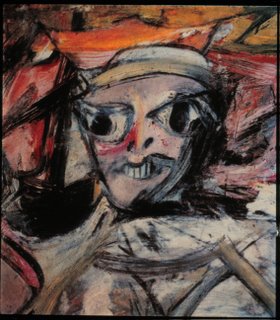

On the other hand, Currin lovingly relishes the curves and bulges of the female figure. He models and renders form, and the figures burst from Currin's silvery palette, reminiscent of the lush "Barry Lyndon." All this care suggests sincerity that neutralizes his ironic tendencies. Compare to David Salle's murky, bland photorealism or Cotton's superacademic, hyperkitsch models, available in chocolate or strawberry. Meanwhile, DeKooning battered women down to fluid scribbles and angular strokes.

Does Currin love women or hate them? Rather, what does he love/hate about women? He said in a Flash Art interview: I don't love women, I just think about them all of the time.

I love to look at women; they stimulate my imagination and not just in a sexual way.

I used to love watching women hobbling in their new shoes down fourteenth street.

I saw myself in them. I get a perspective on myself when looking at a woman, her beauty, her ugliness, her failures.

Six or seven paintings - less than half of the show - are sex pictures. The others are "chick paintings," including a portrait of his fully clad spouse, in "Federal Rachel." Another clothed woman is the fruit-bearing brunette in "The Christian," a hilarious prude suffering the fornicating heathens. More hilarious is "Anna" a Christopher Guest-cast nerd in her late 30s who smiles all too warmly from behind a candlestick and ripe banana.

The clues to a narrative arc are two portraits of Currin's son, Francis, and a future portrait, "2070," where Francis appears as a post-sex old man. This, and the neighboring baby portrait are bookends to the chapters of adult sexual adventure of Francis, something like Hockney's or Hogarth's "The Rake's Progress" - maybe that's what Francis 2070 is reading! Alas, like Father, like Son; Francis likes his whores, but loves his Madonna - again, "Federal Rachel." He may be a womanizer, but our polyester-suited, gallant gentleman still courts his women with white wine and a sunny day.